Understanding Ligamentum Teres Tears: Signs, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

The hip joint is one of the most stable yet dynamic joints in the human body. Its ability to support weight, absorb impact, and allow for a wide range of motion is what makes it essential for athletes and active individuals. Within this joint lies the ligamentum teres (LT) which is a small but increasingly recognised structure that can be a significant source of hip pain and dysfunction when injured.

Though historically thought to have little functional role, modern research shows that the ligamentum teres plays a part in joint stability, proprioception, and pain mediation (Bardakos & Villar, 2009; Cerezal et al., 2010). Tears of the ligamentum teres are being diagnosed more frequently due to advances in hip arthroscopy and imaging techniques. For clinicians, athletes, and clients dealing with unresolved hip pain, understanding LT injuries is crucial.

This article explores the signs and symptoms, mechanisms of injury, diagnostic approaches, prognosis, imaging classifications, and management strategies for ligamentum teres tears.

What is the Ligamentum Teres?

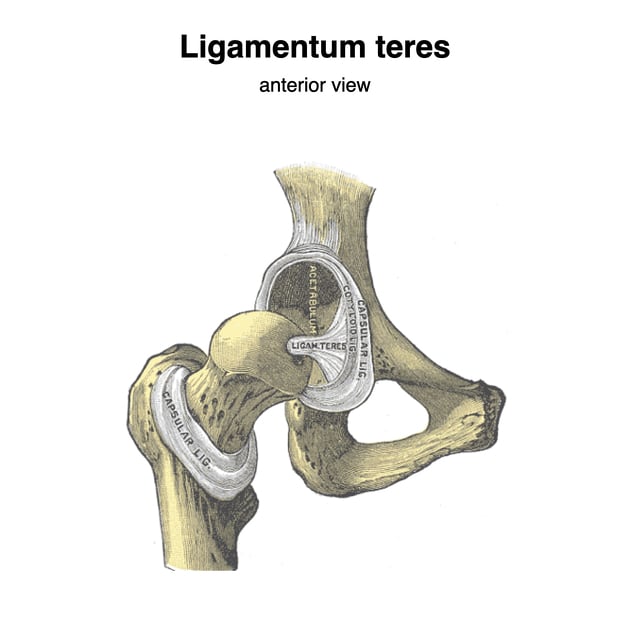

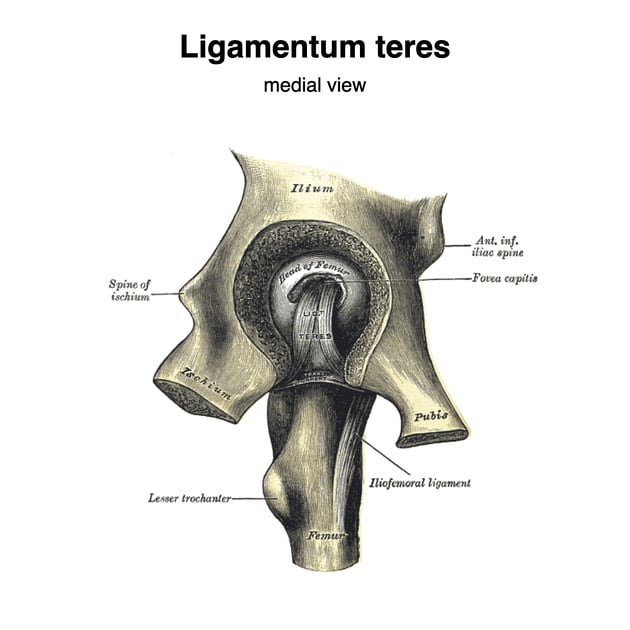

The ligamentum teres is a cord-like ligament connecting the femoral head (thigh bone) to the acetabulum (hip socket). While not the primary stabiliser of the hip, it contributes to secondary stability, particularly in movements that involve combined rotation and flexion/extension (Bardakos & Villar, 2009). It also has a rich nerve supply, which means that when injured, it can be a significant source of pain.

Figure 1. Medial view of the ligamentum teres connecting the femoral head to the acetabulum (Radiopaedia, n.d.).

Figure 2. Anterior view of the ligamentum teres within the hip joint (Radiopaedia, n.d.).

Signs and Symptoms

The presentation of an LT tear is often subtle and can overlap with other hip pathologies like labral tears or femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). Key symptoms include:

- Deep hip or groin pain – Often vague and poorly localised, sometimes described as a “catching” pain.

- Mechanical symptoms – Clicking, locking, or a feeling of instability in the hip (Byrd & Jones, 2004).

- Pain with specific movements – Commonly aggravated by squatting, pivoting, or rotational sports movements.

- Restricted range of motion – Particularly internal rotation and flexion.

- Pain at rest – Some patients report night pain or discomfort when lying flat.

For athletes, LT tears may present as persistent hip pain despite rehab for other suspected conditions, making them tricky to diagnose without imaging or arthroscopy.

Mechanism of Injury

Ligamentum teres tears can occur through traumatic or degenerative mechanisms.

- Traumatic tears: Often linked to sporting incidents involving twisting, pivoting, or falls. High-impact trauma, such as dislocation or subluxation of the hip, can rupture the ligament (Byrd & Jones, 2004).

- Degenerative tears: More gradual, often associated with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), hip dysplasia, or repetitive microtrauma (Cerezal et al., 2010). Over time, repeated stress leads to fraying and partial tearing.

Athletes in pivot-heavy sports like basketball, soccer, gymnastics, and martial arts are at higher risk due to the rotational forces on the hip.

Diagnosis

Clinical Assessment

Clinical examination alone can be challenging due to overlapping symptoms with labral or cartilage injuries. However, tests such as the ligamentum teres test, log-roll test, hip scour test, and resisted straight-leg raise may reproduce symptoms (Braly et al., 2006).

Imaging

Advances in imaging have significantly improved diagnosis:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with arthrography (MRA) is currently the most effective non-invasive tool, allowing visualization of LT tears and associated pathology (Cerezal et al., 2010).

- Standard MRI has limited sensitivity, particularly for partial tears.

- Hip arthroscopy remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis and classification.

Imaging and Arthroscopic Classification Systems

Classification of LT tears helps guide management decisions. Several systems exist:

- Gray and Villar (1997) Classification

- Type I: Complete rupture

- Type II: Partial tear

- Type III: Degenerative ligament

- Botser et al. (2011) Arthroscopic Classification

- Partial tears (fraying or partial rupture)

- Complete tears (full discontinuity of fibers)

- Cerezal et al. (2010) MRI-based system

- Focuses on structural changes (e.g., synovitis, edema, and fiber disruption) to help correlate imaging findings with arthroscopic evaluation.

These systems allow clinicians to distinguish traumatic vs. degenerative patterns and tailor treatment accordingly.

Prognosis

The prognosis for LT tears depends on the severity and associated hip conditions.

- Isolated partial tears may respond well to conservative rehabilitation.

- Complete ruptures are less likely to heal due to the ligament’s poor vascular supply (Byrd & Jones, 2004).

- Coexisting conditions such as labral tears or FAI may complicate recovery and require surgical intervention.

With appropriate management, many athletes can return to sport, though recovery time varies between 8–24 weeks depending on treatment.

Management Strategies

1. Conservative (Non-Surgical) Management

First-line treatment often involves physiotherapy and activity modification:

- Load management: Reducing aggravating activities (e.g., pivoting, deep squatting) while maintaining general fitness.

- Strengthening programs: Focus on hip stabilisers—gluteus medius, deep rotators, and core.

- Range of motion (ROM) restoration: Gradual mobility exercises while avoiding extremes of rotation.

- Neuromuscular control training: Proprioceptive drills to restore stability.

- Pain management: NSAIDs or guided injections (if inflammation is present).

This approach is most effective in partial tears or degenerative cases without major instability.

2. Surgical Management

For cases not responding to rehab or involving complete tears, hip arthroscopy is the gold-standard intervention:

- Debridement – Removal of torn fragments, often effective in reducing mechanical symptoms (Haviv & O’Donnell, 2011).

- Thermal capsulorrhaphy – Shrinking and tightening tissue to restore stability.

- Ligament reconstruction – Rare but considered in cases of gross instability, often using grafts.

Arthroscopic treatment has shown promising outcomes, particularly in athletes, with improved pain scores, function, and return-to-play rates (Botser et al., 2011).

Physiotherapy Role in Rehabilitation

Post-diagnosis or post-surgery, physiotherapists play a crucial role in recovery:

- Phase 1: Acute management – Pain control, protected ROM, gradual weight-bearing.

- Phase 2: Strength and control – Progressive strengthening of glutes, deep rotators, and core stabilisers.

- Phase 3: Functional rehab – Sport-specific drills, plyometrics, and change-of-direction training.

- Phase 4: Return to sport – Objective testing (strength ratios, hop tests, agility tests) to ensure safe return.

For athletes, rehab should be individualised with emphasis on movement quality, not just strength gains.

Key Takeaways

- The ligamentum teres is an increasingly recognized source of hip pain.

- Tears may result from trauma or degeneration and are often associated with other hip pathologies.

- Diagnosis requires advanced imaging (MRA) or arthroscopy, as clinical signs are often non-specific.

- Classification systems (Gray & Villar, Botser, Cerezal) help guide treatment choices.

- Conservative physiotherapy management can be effective in partial tears, while arthroscopic debridement or reconstruction is often required in complete ruptures.

- A structured rehabilitation program led by physiotherapists is essential for return to sport.

Abe Ofosu

Physiotherapist (APAM)

References

Bardakos, N. V., & Villar, R. N. (2009). The ligamentum teres of the adult hip. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 91(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.21074

Braly, B. A., Beall, D. P., & Martin, H. D. (2006). Clinical examination of the athletic hip. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 25(2), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2006.01.001

Byrd, J. W., & Jones, K. S. (2004). Traumatic rupture of the ligamentum teres as a source of hip pain. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 20(4), 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2004.01.007

Cerezal, L., Kassarjian, A., Canga, A., Dobado, M. C., Montero, J. A., Llopis, E., Rolon, A., & Perez-Carro, L. (2010). Anatomy, biomechanics, imaging, and management of ligamentum teres injuries. Radiographics, 30(6), 1637–1651. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.306105516

Haviv, B., & O’Donnell, J. (2011). Arthroscopic debridement of the isolated ligamentum teres rupture. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 19(9), 1510–1513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-011-1663-1

Radiopaedia. (n.d.). Ligamentum teres of the hip. Retrieved August 29, 2025, from https://radiopaedia.org/articles/ligamentum-teres-of-the-hip